A Short History of Batto-jutsu in America (Part 2)

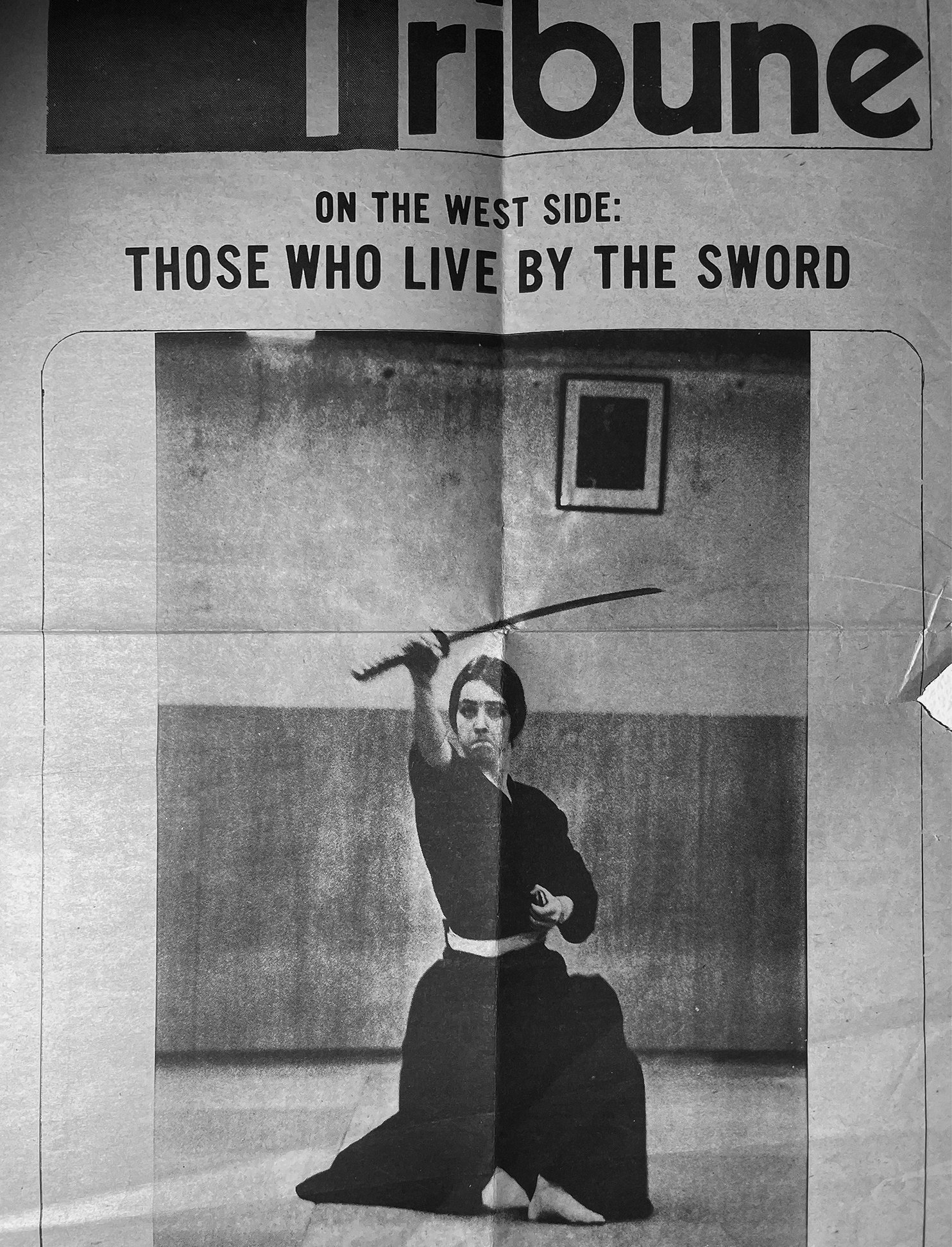

Manhattan Tribune newspaper article featuring iaido at the Kokushi Budo dojo, American Buddhist Study Center, NYC (1971, uncredited)

Preface to Part 2

This essay is part two of three and covers the years from 1970 to 1989, a challenging time in the development of iaido / battodo worldwide. The predominant iai ryuha practiced internationally at this time were Muso Shinden-ryu and Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu – sometimes taught in an orthodox manner and sometimes with variations. The arrival of the ZNKR Seitei Gata in 1969 expanded iai practice in US kendo dojos but reduced the number of kendoka studying MSR and MJER. In Japan the ZNIR was (and is) the largest iaido practiced, followed by the ZNKR. Outside of Japan that relationship was inverted.

As the variety of iaido ryuha grew internationally, fragmentation of ryuha in Japan made tracking of individual instructors who came to the US representing those ryuha difficult if not actually impossible. Going forward this essay will focus on iaidoka who led major organizations or dojo, although major may be an oxymoron when we discuss iaido. I also note that for the purposes of this article the terms iaijutsu, iaido, battojutsu, battodo and kenjutsu will be intermingled.

Part 2: Iaido and Batto-jutsu in America in the 70s and 80s

As noted in part one, beginning with the Korean War (1950-53), Japan served as the military staging ground in Asia for US proxy wars with communist China and Russia. The US invested heavily in rebuilding Japan’s economy and on this foundation, Japan marked its reemergence on the world stage by hosting the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. During the Vietnam War (1964-75), Japan, like Germany, regained a place of preeminence among the world economies. In 1972 Japan again hosted the Olympics (in Sapporo) and after the 1973 oil crisis, was able to express its ascendancy as an international industrial and manufacturing powerhouse with the third largest GDP worldwide just behind the US and the Soviet Union. Japan was viewed with both fascination and fear as Americans tried to understand how it had achieved its rapid success. In this context interest in Japanese martial arts grew exponentially.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were also politically tumultuous as nations aligned on either side of the Cold War and as anti-colonial sentiment in opposition to Western wars fought in third world nations matured. Protests in Japan were motivated by both the anti-nuclear arms movement, and by an anti-colonial sentiment. This effected swords-arts practice disproportionately as some ryuha were viewed as counter-cultural and others as militaristic.

“Traditional Japanese martial arts were perceived as a relic from an unwanted past. People wanted to distance themselves from anything to do with martial arts, let alone one that taught the use of Japanese swords, a symbol of the Imperial military which led Japan to shame. ”

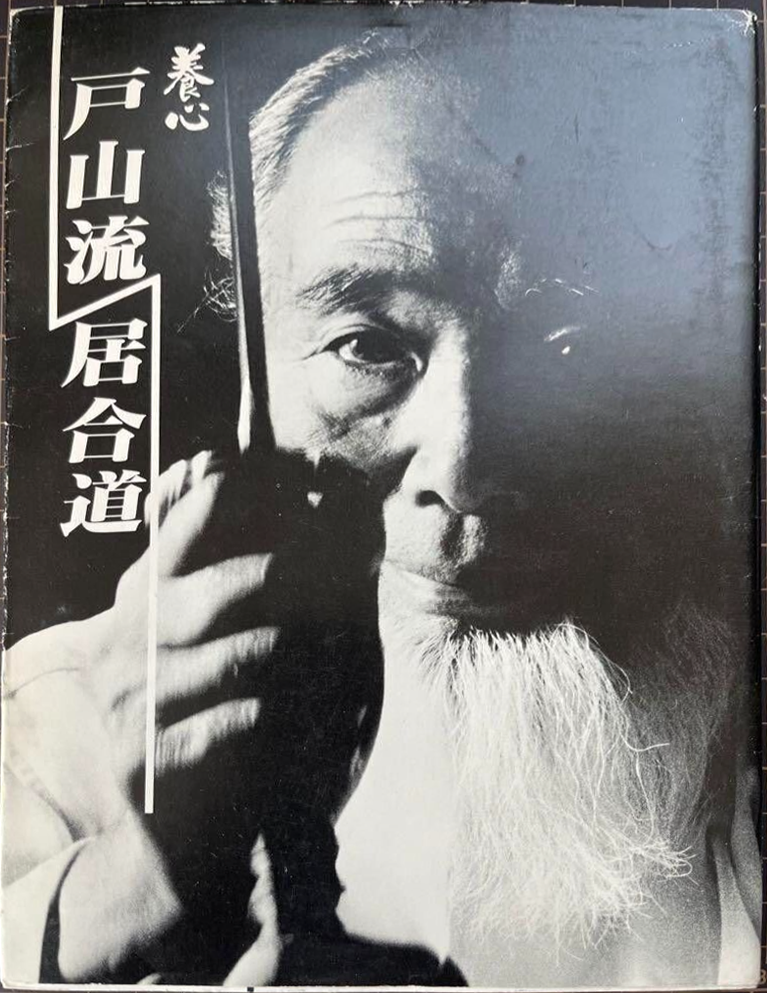

Interpreted as antithetical to the post-war spirit of iaido, combat oriented battojutsu and the practice of suemongiri in particular were frowned upon. Iwata Norikazu sensei, a highly ranked kendoka and one of Oe Masaji sensei’s senior students, publicly repudiated the practice of using iai for combat purposes (Power, 1998). Esaka Seigen sensei, a co- founder of the ZNIR, student of Kono Hyakuren sensei and a major figure in MJER through the Torao Den, also repudiated the use of the sword as a tool or for cutting. For Esaka sensei the sword was to be considered a religious artifact. As a result of this debate and the anti-military sentiment of the times, Toyama-ryu was languishing. In response Nakamura sensei sought the help of Inoue Kyoichi Munenori, the soke of Hontai Yoshin-ryu Heiho. Munenori sensei suggested to Nakamura sensei that he write a book.

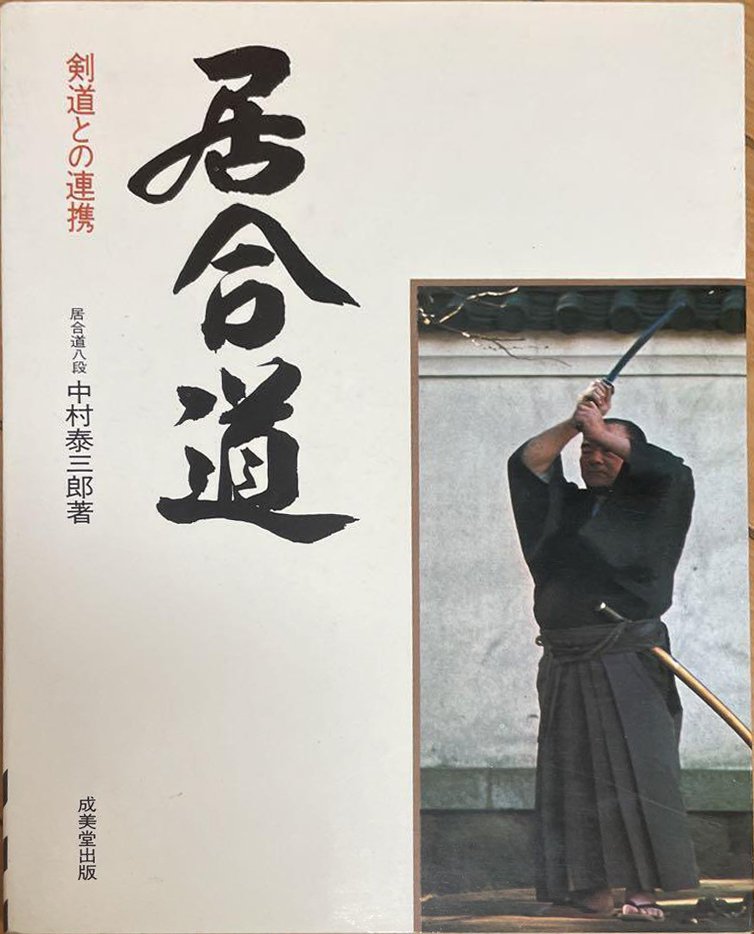

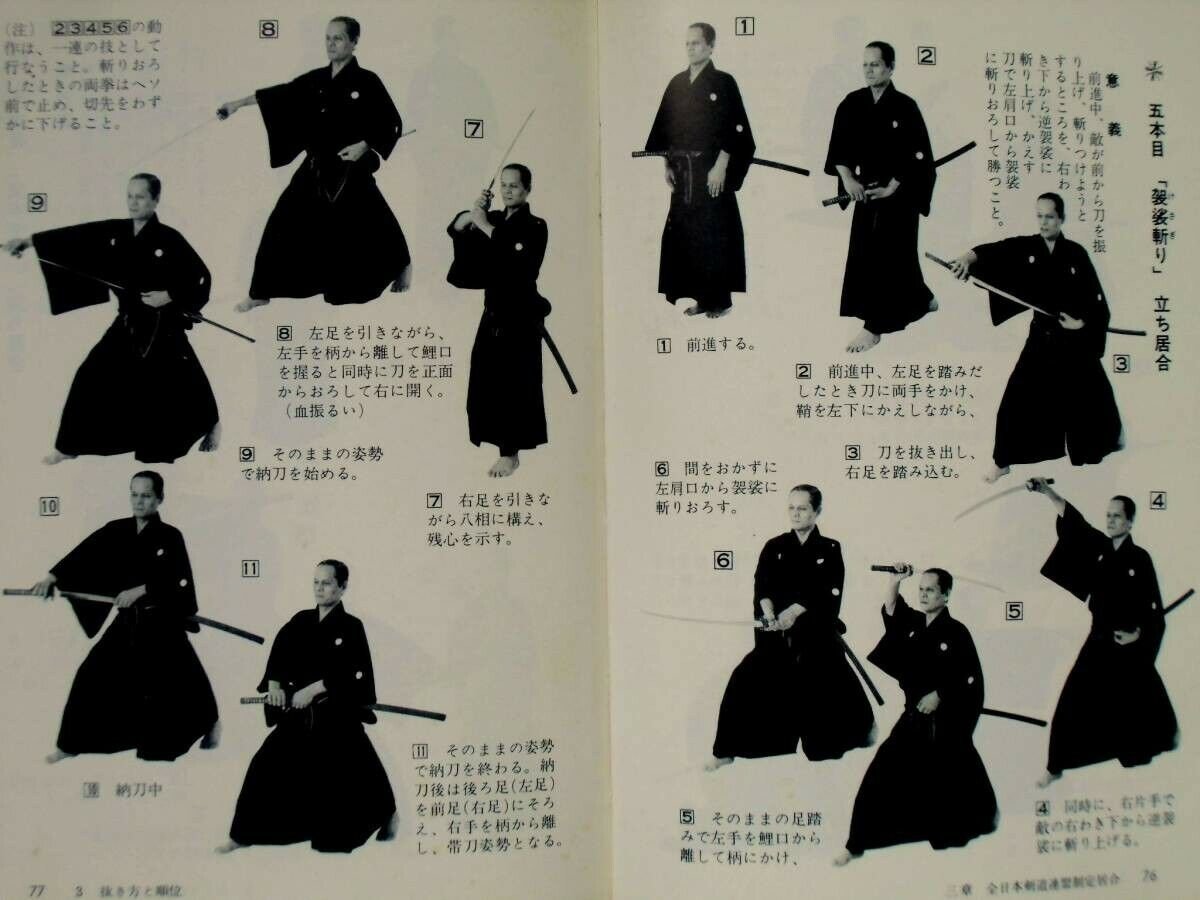

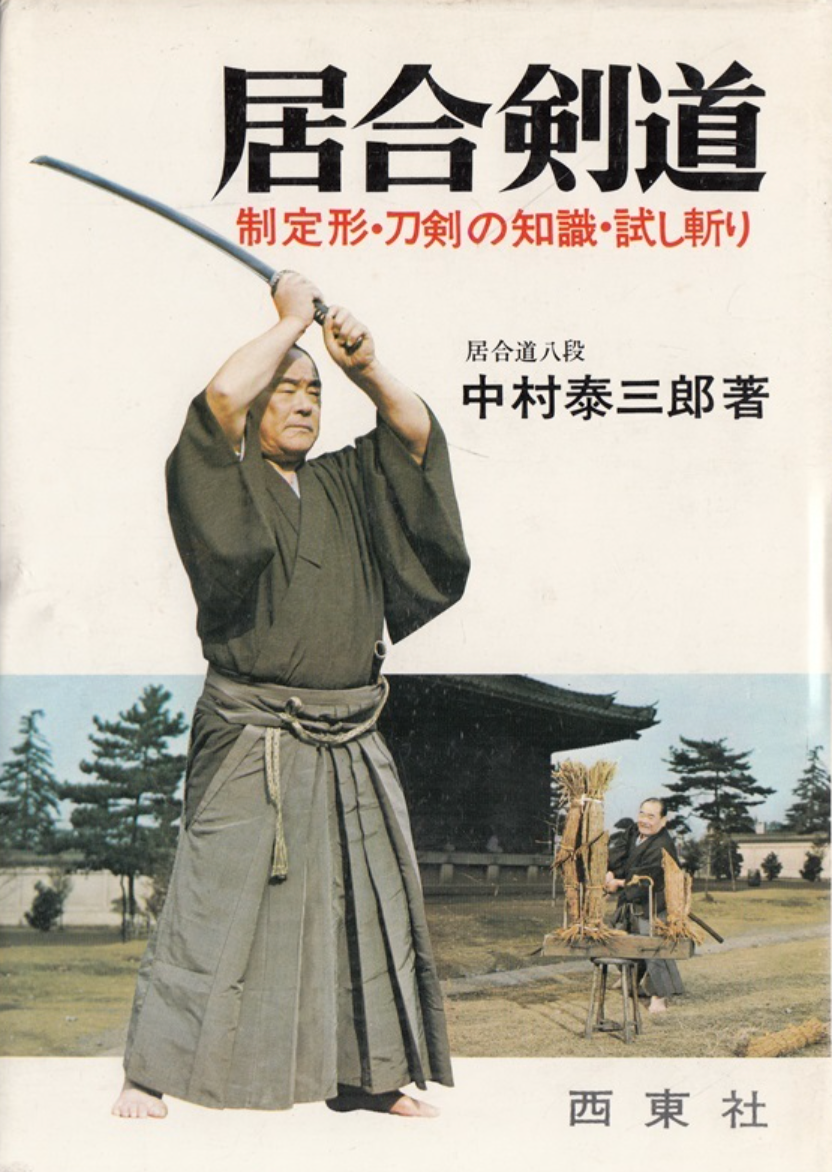

Nakamura sensei wrote not one but two companion books, Iaido and Iai-Kendo Seiteikei Tameshigiri, (Seitousha, Japan) both published in 1973. The first is essentially a Toyama-ryu manual with photos and instructions for the kata, it also included Nakamura’s training and strengthening routines. The second expressed Nakamura’s thoughts on tameshigiri as a necessary aspect of iai practice. These books were not available in the US but were known to Americans who studied budo in Japan.

Yamaguchi Yuuki and Morinaga Kiyoshi sensei both wrote books as well, Yoshinori Toyama-ryu Iaido (Japan, 19??) and Dai Nippon Toyama Ryu Iaido (Japan, 1982) respectively, although both are difficult to near impossible to find. I note that in the 1970s all three sensei referred to their arts as iaido not battojutsu.

Substantial changes were happening elsewhere within the Japanese iai community. In the early 1970’s the last direct students of the Famed Tosa Fighting Men of Kochi Prefecture began to pass. Fukui Harumasa sensei in 1971; Masaoka Katsutane sensei in 1973; Kono Hyakuren sensei in 1974; Uno Mataji sensei in 1975; Yamamoto Takuji sensei in 1977 and Yamamoto Harusuke sensei in 1978. After Oe Masaji sensei’s passing the Tosa school had fragmented with multiple holders of Kongen no Maki (根元之巻) claiming the title of Eishin-ryu Soke. The passing of Masaoka and Kono sensei were particularly impactful as Masaoka sensei had been recognized as SoShihan by the ZNKR and DNBK, and Kono sensei by the Seito lineage and the ZNIR. With their passing the ZNIR MJER line split again into four groups including the Nihon Iaido Renmei and Dai Nihon Iaido Renmei (In 2010, another split occurred - World MJER Iaido Federation).

This fragmentation shouldn’t impact our appreciation of any individual line of transmission, but we should keep in mind that in the 1950’s when Masaoka sensei formed the iai division of the ZNKR, a number of kenshi associated with Kono sensei’s ZNIR followed Masaoka sensei to the ZNKR. This caused friction, but more importantly may have reflected differing philosophical views about how iaido should be practiced which also impacted the manner in which MJER was transmitted to the US, with multiple sensei representing different philosophies coming to the US over the years.

In a similar vein, after the war, three separate organizations had been created to represent Toyama-ryū Iaido.

In Hokkaido, the Greater Japan Toyama Ryu Iaido Federation was established by Yamaguchi Yuuki; in Kansai (Kyoto- Osaka area), the Toyama Ryu Iaido Association was established by Morinaga Kiyoshi, and in Yokohama, the All Japan Toyama Ryu Shinko-kai was established by Nakamura Taizaburo. Each of these organizations was autonomous and retained its own set of waza, for example the Yamaguchi-ha branch curriculum included sword versus bayonet kumitachi, which Nakamura sensei had stopped teaching after the passing of his eldest daughter. At this time no flavor of Toyama- ryu was being taught in the US or to any Americans.

The fading stigma of the war, Japan’s economic resurgence, and no doubt the many books helped Toyama-ryu achieve some growth in popularity, but in 1976 Nakamura sensei and Sato Shimeo sensei participated in a battodo embukai in Kyoto that was to have long-term consequences for the three ryuha of Toyama-ryu.

“Morinaga Sensei, Yamaguchi Sensei and Nakamura Sensei met for the first Zen Koku Taikai. These three were planning to unite the three Toyama ryu styles. After the Taikai there was a closing party, where Nakamura Taisaburo Sensei distributed cards naming him the Toyama ryu Soshihan or head instructor. Morinaga and Yamaguchi senseis remarked that they had not discussed granting the rank of soshihan to Nakamura Taisaburo. They were after all his teachers!”

Perhaps in reaction to his misstep in Kyoto, Nakamura sensei created the Zen Nihon Toyama Ryu Battojutsu Shinko Renmei with Tokutomi Tasaburo as chairman. In 1977 Nakamura sensei held the first All-Japan Toyama Ryu Tameshigiri Taikai in Yokohama. In 1979 that group was replaced by the Zen Nihon Toyama-ryu Iaido Renmei with a fellow instructor from the Toyama Gakko, Masudo Hideo sensei, serving as the ZNTIR’s first president and Kouno Kenzo as chairman.

in 1980 to create a single organization “across the boundaries of the style / ryuha, gather in one place to promote mutual friendship and technical studies and to spread and develop the Batto Do”, Nakamura created the Zen Nihon Batto Do Renmei with himself as chairman and Ueki Seiji sensei as its first president. The ZNBDR offered a ha-agnostic seitei kata set and sponsored annual taikai that all batto practitioners could participate in.

Popularizing Iaido in the West

Kurosawa Akira and George Lucas with model of an AT-AT walker (Lucasfilm)

As in the past a steady stream of jidaigeki chanbara films played an outsized role in popularizing Japanese swords arts in the West. International film audiences were treated to Mifune Toshiro’s return as his ronin character with his production, Machibuse (Toho, 1970) as well as in Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (Daiei, 1970). Other chanbara films distributed on the international market included Uchida Tomu’s Swords of Death (Toho, 1971); Ozawa Keiichi’s The Hunted Samurai (Toho, 1971); Fujita Toshiya ‘s Lady Snowblood (Toho, 1973); actor/director Misumi Kenji’s The Last Samurai (Okami yo rakujitsu o kire, Shochiko, 1974), and Fukasaku Kinji’s Shogun’s Samurai (Toei, 1978). International audiences were also introduced to samurai series with the highly popular Zatoichi, Lone Wolf and Cub, and The Yagyu Conspiracy.

While the impact of Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon (Warner Bros., 1973) on the appeal of all Asian martial arts can’t be understated, in the 1970’s the film that probably had the biggest impact in introducing kenjutsu and eastern philosophy to the West was one based on Kurosawa Akira’s Hidden Fortress – that was George Lucas’s and Lawrence Kasdan’s Star Wars (Lucasfilm, 1977). Although perhaps setting some unrealistic expectations, the film gave iaido study a boost with its lightsabers; a yoroi-clad cyborg named Darth Vader, and the Jedi Knights, a not-so-subtle combination of samurai with the European Knights Templar who in turn used a form of ki / energy called the Force (for a more in-depth analysis see also Wave People, Donahue, JAMA, 1994).

Star Wars was followed by The Empire Strikes Back (1980, Lucasfilm) and Return of the Jedi (1983 Lucasfilm), both of which deepened the lore and improved on the swordplay with 6’1” fight choreographer Bob Anderson, an Olympic fencer, donning the Darth Vader costume in place of 6’7” David Prowse due to insurance restrictions. Anderson went on to choreograph the excellent duels in The Princess Bride, The Mask of Zorro, and Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trlilogy.

During this time non-Japanese filmmakers joined in the samurai game with Red Sun (Les Films Corona, 1971), an Italian financed spaghetti Western that was released to great success in Japan and good returns in the US. The film starred Mifune Toshiro uniting the Western gunslinger and samurai chanbara genres, although perhaps not in a way that John Ford or Kurosawa Akira might have imagined. Kenjutsu was also featured in Sydney Pollack’s The Yakuza (Warner Bros., 1974), described as a “The Godfather meets Bruce Lee” in reviews. It was not a perfect film by any means, but one in which the use of swords in a modern setting seemed completely appropriate. Yakuza was a failure at the box office, but it paved the way for other American films that integrated samurai characters into their storylines.

The 1980’s were replete with such films — among them The Bushido Blade (Rankin/Bass, 1981); Enter the Ninja (Cannon Group, 1981); The Challenge (Embassy, 1982), and Ridley Scott’s Black Rain (Jaffe-Lansing 1989). Black Rain featured a small role with Obata Toshishiro sensei, his first in the US.

Arnold Schwarzenegger fight training with Yamazaki Kiyoshi

Two films that probably had an outsized impact on Americans interest in iai were the cult classics Conan the Barbarian (Laurentis, 1982) and Highlander (Thorn, 1986), both of which brought some interesting characters to iai dojos around the country. Although neither film is about samurai, both have fights or fighters that wield katana. Directed by kendoka John Milius, for Conan, Arnold Schwarzenegger and the other principal actors studied three times a week for a full year with Yamazaki Kiyoshi, a highly ranked karateka who was also adept at judo, aikido and iaido. He worked on both their sword handling and their zanshin. The duels in Highlander were choreographed by Bob Anderson.

It should be noted that Kurosawa Akira’s Kagemusha (Toho, 1980) and Ran (Toho, 1985) were both international films in that they were made with American and international financing.

The popularity of iaido can also be charted through the growth in English language publications. In the 1970s and 80s there were 15 books published in Japan on Muso Jikiden Eishen-ryu although none in English (granted most of the Japanese texts were written by only four authors, Kono Byakuren, Masaoka Katsutane, Fukui Torao Seizan and K. Taizan). During the same period there were five Japanese books published on Muso Shinden-ryu, three in French, and only one in English — Malcolm Shewan’s Iaido, which is actually a dual language English / French publication. There were nine books written in Japanese on a variety of other sword arts including ZNKR Seitei, Toyama-ryu and Katori Shinto-ryu and eleven on the same subjects in English. These books were joined by 21 more titles in English that covered sword art history, and philosophy, and seven titles specifically on nihonto themselves. This speaks both to the launch of the ZNKR Seitei waza and a developing depth of interest in Japanese sword arts in general.

One book with a huge impact was certainly Musashi Miyamato’s Go Rin no Sho — The Book of Five Rings translated by Victor Harris and published by Overlook Press in 1974. Harris was an afficionado of both weapons and Japanese culture and a curator in the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum. In turn Musashi’s insights proved popular and caught on not only with Western kenshi, but, buoyed by of Japan’s growing economic ascension, with businesspeople as well. Musashi joined Machiavelli and Sun Tzu as required texts in business strategy. No matter how one feels about Sengoku period samurai texts, or the samurai who wrote them, their publication revolutionized our conception and appreciation of budo. Problematic as they can be, books from that era are considered foundational not only for technique but as philosophy as well. It should be noted that since the 1970s, more precise and annotated translations of Go Rin No Sho have been published.

“Draeger was primarily concerned wit the dilution of combative efficacy in modern interpretations of the bugei, and so he directed his criticism against those arts that he felt were most infected with that particular virus.”

Nakamura sensei’s batto-jutsu was introduced to English speaking audiences in Donn Draeger’s three volume series, Martial Arts and Ways of Japan (Weatherhill, 1973-74). These books are not manuals or martial arts surveys a la Zen Combat, but rather well-researched commentaries on the Japanese martial arts in their social and political context. This series followed Draeger’s Asian Fighting Arts (Kodansha, 1969), allowing him to go into greater depth on each art discussed. In the first chapter of the third volume, Modern Budo and Bujutsu, Draeger introduced Nakamura sensei, Toyama-ryu and Nakamura-ryu to English speaking audiences and in keeping with Draeger’s views on budo, Draeger expressed appreciation for both his friend, Nakamura sensei, and sensei’s arts.

In the 1970s the home video cassette revolutionized martial arts instruction led by a documentary entitled Einaru Budo (Budo Eternal), Masuda Hisao and Tokutomi Tasaburo (one of Morinaga sensei’s students). Surveying gendai budo and released in the US with the unfortunate title, Budo: The Art of Killing, the documentary presents somewhat naive concepts similar to those in Inazo Nitobe’s book, Bushido, The Soul of Japan, nominally tracing a correlation between samurai bujutsu and gendai budo. Nevertheless, it is a worthwhile documentation of several arts and showcased Nakamura sensei, Matsushita Shuji, Obata Toshishiro, Toyoshima Kazutora, Koide Tomoo, and work of swordsmith Amata Akitsugu for Western audiences for the first time. Tokutomi sensei and Nakamura sensei face off near the end of the video, and standing in for Tokutami sensei, Obata sensei, a Tokyo-based actor and stuntman, had an unfortunate beheading at the very end of their duel. Not distributed in the US until 1982, it found success internationally in the home video market.

In 1982, to address the demand of a curious American market, Joseph S. Jennings, an Isshin Ryu katateka, launched Panther Productions, producing literally hundreds of how-to martial arts instruction videos, although it would be several more years before Panther produced its first iaido video.

Following Einaru Budo, Nakamura sensei published his third book, Nihonto Tameshigiri no Shinzui, in 1980. Also available only in Japanese this book was almost twice the size of his first two and is a comprehensive introduction to both Toyama-ryu Battodo and Nakamura-ryu Happogiri Battodo. The cover features a still image from Einaru Budo, as would all his subsequent books, again speaking to the documentary’s importance in promoting Nakamura sensei’s arts. The book is also a very good general introductory text to Japanese sword arts practice, and to an extent set a standard for books that followed with extensive information on etiquette, sword care and warm-up exercises. In the book Nakamura sensei is frank in sharing his views on the evolution of iai practice and other ryuha, although those opinions may take liberties in their interpretation of pedagogical and practical training. Nevertheless, his insights carry the weight of his military experience.

A still frame from Budo as the cover image for Nakamura sensei’s third book.

1980 was also the year that saw James Clavell’s Shogun (Paramount) mini-series starring Mifune Toshiro as Lord Toranaga (Tokugawa Ieyasu). Based on Jame’s Clavell book, Shogun (Delacorte, 1975) it was broadcast on American television over five nights and also released as a theatrical cut in the US and Europe.

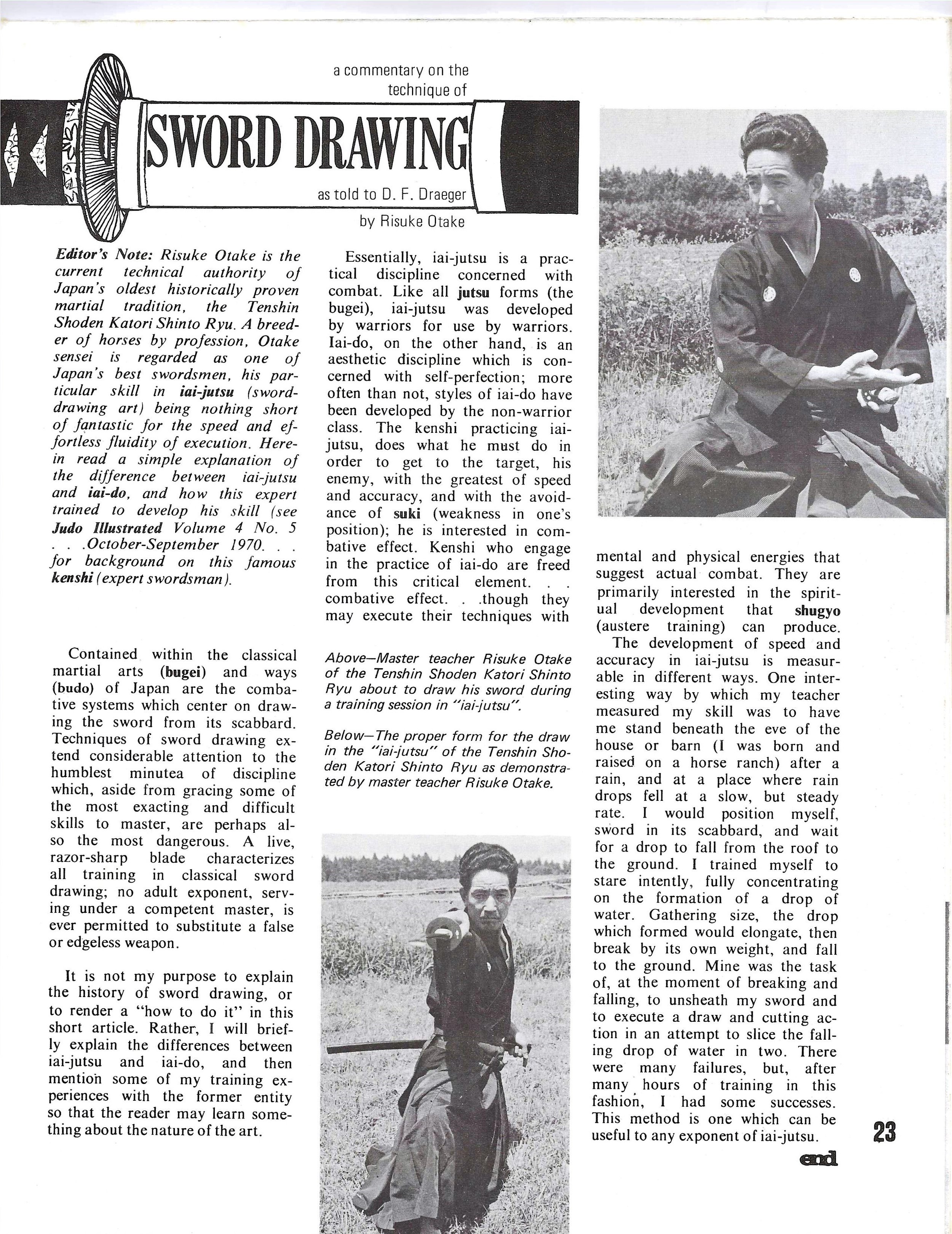

Among other important books published during this time period, E. J. Harrison’s The Fighting Arts of Japan of 1911 was republished in the US in 1982, and that same year Draeger and Dr. Warner’s Japanese Swordsmanship (Weatherhill) was published. Draeger and Warner’s book is more than simply a manual as it discusses the broad tapestry of Japanese swords arts with Draeger’s informed and opinionated commentary throughout, and similar to Nakamura sensei’s Nihonto Tameshigiri no Shinzui, it includes information on a range of sword related necessities and practices, including sword care with illustrative photos of Otake sensei, and Mitsuzuka sensei performing reiho as well as ten kata of the ZNKR Seitei-gata. Japanese Swordsmanship was and is an invaluable reference for all kenshi.

1982 was also the year William Scott Wilson wrote the first of his many books, Ideals of the Samurai: Writings of Japanese Warriors (OHara), based on his graduate school research. Wilson soon followed with translations of the Hagakure (Hidden by Leaves) by Yamamoto Tsunetomo in 1983; Budoshinshu: The Warrior's Primer by Daidōji Yuzan in 1984, and then probably his most popular work, Takuan Soho’s Fudōchi Shinmyōroku - The Unfettered Mind: Writings from a Zen Master to a Master Swordsman (Kodansha). Wilson’s translation remains the sole and definitive edition and he subsequently made a career of studying and writing about all things samurai.

Dave Lowry’s Autumn Lightning, the Education of an American Samurai (Shambhala), about his study of Yagyū Shinkage-ryū under Ryokichi Kotaro was published in 1985, and in 1986 Lowry wrote a bokken training manual based on Yagyu Shinkage-ryū kata and kumitachi for Ohara Publications.

Also in 1986, the previously mentioned Iaido: The Art of Japanese Swordsmanship (Crompton) by Malcolm Tiki Shewan sensei focused on Muso Shinden-ryu but offered a comprehensive introduction to iai, with information on uniform, swords, reiho, tameshigiri and illustrations of MSR kata. Having begun his iai studies in 1970; earning high-ranking in MSR and Ryūshin Shouchi Ryu as a student of Kan, Otani and Mitsuzuka sensei, and having studied traditional Japanese metallurgy and sword smithing, Shewan sensei is still teaching today.

1986 was also the year Yagyu Muneyori’s The Sword and the Mind was translated by Hiroaki Sato for Overlook Press, and an English language edition of Otake sensei’s three volumes on Katori Shinto-ryu, The Deity and the Sword (Japan Publications Trading Co.) was released in 1988. These books marked an expanded interest in both budo and koryu swords arts.

The Hop-lite Newsletter remained in publication well until the Internet era.

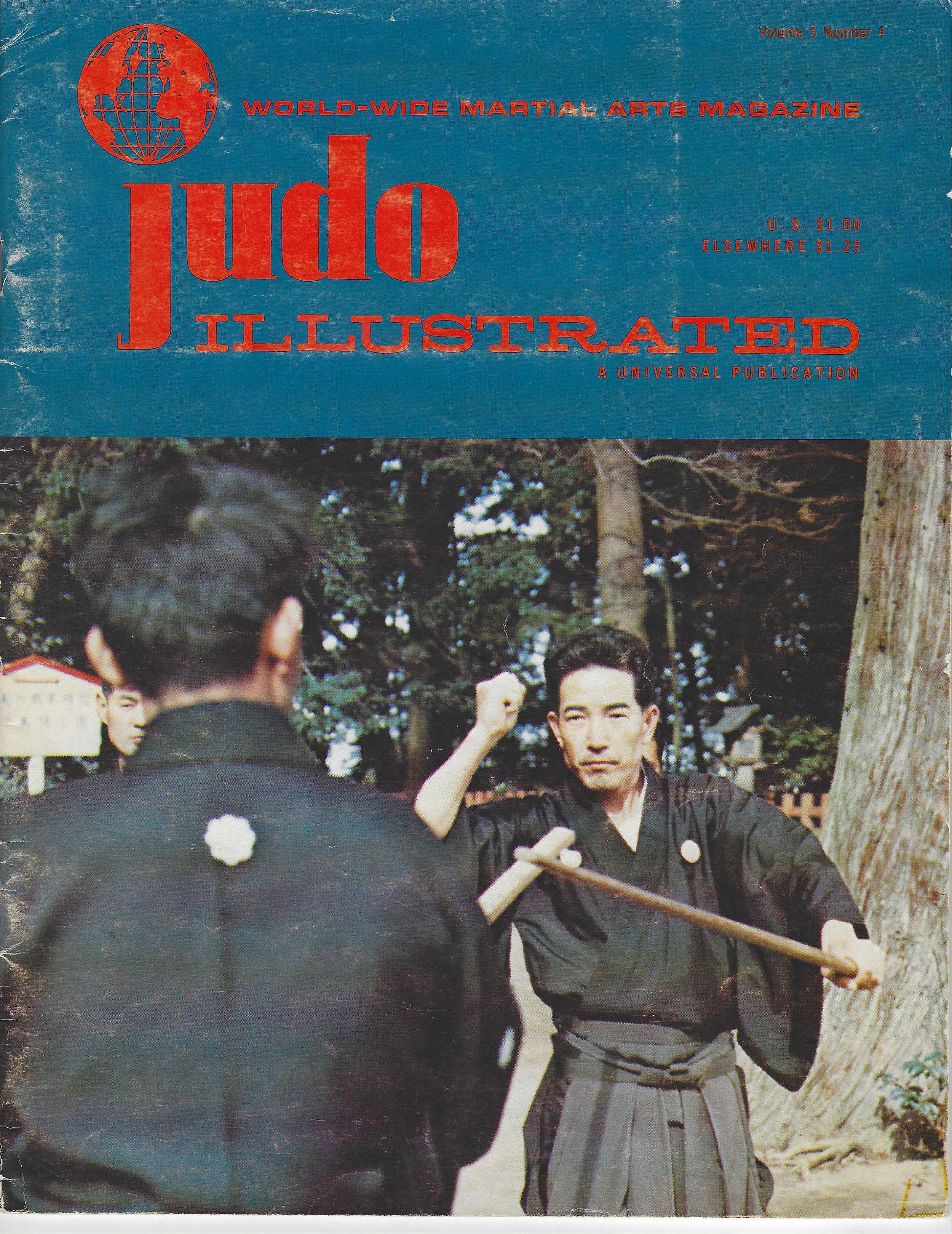

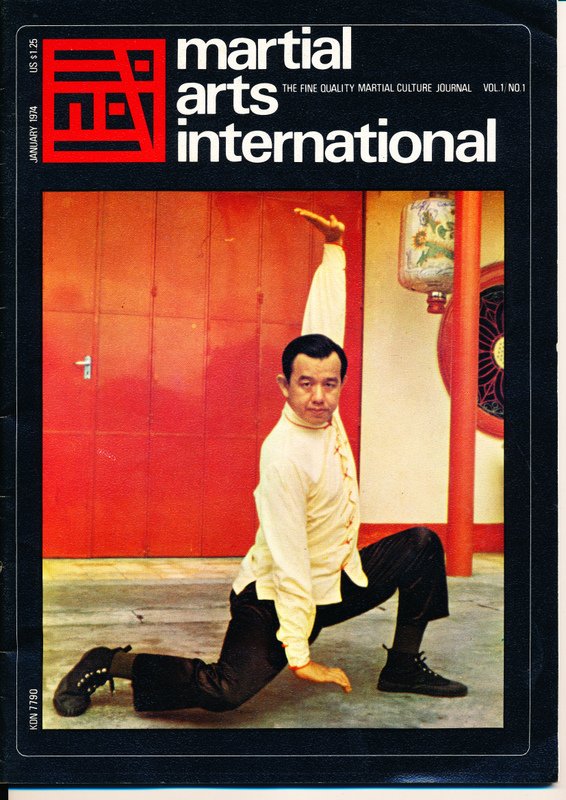

In addition to books, films and videos, martial arts were explored in greater breadth and depth through magazines, journals, and newsletters. Building on Black Belt Magazine, Donn Draeger may be credited with initiating this with his 1971 attempt to revamp Judo Illustrated as a more general martial arts magazine. This was followed in 1974 by the creation of journal Martial Arts International, edited by Quentin Chambers with Draeger as the technical editor and contributing writer.

This was later followed by his International Hoplology Society’s Hoplos journal. Unfortunately, Hoplos was launched in 1980, only two years before Draeger’s untimely death from cancer. Hoplos and the corresponding Hop-lite newsletter survived Draeger’s passing and also inspired others to create newsletters and journals along a similar vein.

The Bujin magazine was published from 1977-1983 and focused mostly on kenjutsu but included other Japanese martial arts. Its founder and editor, Fredrick Lovret, was a controversial figure in the American kenjutsu community. After serving in the Navy from 1959 to 1974, Lovret settled in San Diego and taught an afore unknown art, Itto Tenshin Katori Shinto-ryu. At the same time Lovret was a beloved teacher and was also author of several books including The Way and The Power: The Art of Japanese Strategy (Paladin Press, 1987), which is his most lasting work. At the "request" of Otake Risuke sensei, Nyle Monday relayed to Lovret to cease use of the name Katori Shinto-ryu(Monday, 2023). Suffice to say Lovret was not the only self-appointed head of an unknown Japanese martial art.

In addition to scholarly newsletters and journals Draeger sensei can also be credited with initiating annual martial arts seminars in the US with his Camp Bushido. Originally an annual judo camp, in 1970 Draeger expanded the subject matter, including what may have been the first demonstration of Katori Shinto-ryu in the US.

Camp Bushido flyer (courtesy of Nyle Monday)

Another development that helped iaido’s popularity was the arrival of mogito into the US market. Known here as iaito and initially available from only one company, Meirin Sangyo Ltd., of Sapporo, Hokkaido. Meirin Sangyo was followed by several Seki City manufacturers (e.g., Igarashi / Nosyudo, Minosaka, Sumita Token and Fujiwara Kanefusa, et al). We can appreciate that iaido practice steadily became more popular once relatively inexpensive zinc-aluminum mogito became available. Novices could not only purchase affordable katana but do so with less fear that they would cut themselves.

The availability of affordable katana spurred an interest in sword furniture as well. In 1979, the Japan Society staged a Japan Festival that featured a wide array of Japanese culture, arts, and crafts. This included an exhibition of tsuba and koshirae from the Cooper Hewitt Museum’s collection. The show included only 44 pieces from a collection of over 600 tsuba and approximately 800 other mountings. All of these had been donated to the Cooper Hewitt in 1936 by the estate of George Cameron Stone, along with over 3,500 pieces that went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1982 Rev. Kan contacted Isuka Kunio (1939-2020), a nihonto collector and aficionado living in New York, to ask his help to help bring members of Japan’s NBTHK to visit and speak in the US. In 1983 NBTHK scholars came to NY and held an exhibition and lecture at the Ken Zen Institute. This event led to the founding of the Kenzan Japanese Nihonto Club, which in turn merged with the Japanese Sword Society to become the New York Token Kai initially led by Prough sensei.

“More sword fittings are on display at the Brooklyn Museum, 188 Eastern Parkway, in an exhibition called “Japanese Sword Fittings from the Sasano Collection.” On loan from Masayuki Sasano of Tokyo, the 100 fittings are decorated with mythological subjects, landscapes and motifs taken from nature and daily life; they date from the Tomb Period (fifth and sixth centuries) until 1876, when the Japanese Government issued a ban on wearing swords as part of a modernization program.”

Practice in the US

On the West Coast growth in iaido was led by a number of American and Japanese sensei, including Walter Takeshi Yamaguchi, a student of Tiger Mori sensei who served on the Board of the AUSKF, the SCKF and helped found the Northern California and Southern California Iaido Associations; Arthur Ichiro Murakami, another student of Tiger Mori who served as President of the AUSKF; Frank Koji Fukawa; Henry Shigeru Asai, and Dennis Ralutin, among others.

On the East Coast, similar growth was led by Kan Shunshin, Daniel T. Ebihara, Otani Yoshiteru, Joseph Bass, Kanai Mitsunari, Shozo Kato, Tsuyoshi Inoshita and Kataoka Noboru, a student of Yamamoto Harusuke sensei who founded the New York City Kendo Club in 1978 teaching kendo and Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryū iai.

These dojo produced the East Coast’s first generation of trained-in-America iaido sensei including Phil Ortiz, Art McConnell, John Prough, Guy Rico, John Denora, Art McConnell, Malcolm Shewan, Pam Parker, Paul Sylvain and Deborah Klens-Bigman, all of whom became adept at multiple budo. Otani’s school produced not only teachers, but also scholars like Shewan and Klens-Bigman sensei who explored and wrote on budo history and practice. Otani sensei’s students at that time also included actors Peter Weller and John Driver who were included in a 1976 article on the Iaikai dojo written by Tom Buckley for The New York Times.

Takeshi Mitsuzuka sensei (Didier Boyet)

The Ken Zen Institute and the Iaikai operated under very different models. Ken Zen had a permanent home and a formal dojo while the Iaikai had begun at the McBurney YMCA, and sometimes had a fixed home but more often than not has operated out of theater and dance rehearsal spaces. Both models are also common in Japan. During this time Otani sensei’s dojo evolved from the Iaikai to the Japanese Cultural Center, offering a wider array of Japanese martial arts and liaisons with other Japanese carts and culture. Deborah Klens-Bigman notes that Otani Sensei promoted an assortment of Japanese culture and “seemed to know everyone in the Japanese community.”

During these years Otani sensei also taught martial arts at the West Point Military Academy. In addition to Muso Shinden- ryu, Otani sensei taught a number of iaido styles that he learned during annual visits to Japan. These included Toyama- ryu and Teshin Sho Jigen-ryu and were taught with and sometimes without permission.

Otani also invited guest sensei from Japan to come teach at the Iaikai, including in August 1976 for a two week intensive, Mitsuzuka Takeshi sensei, who was then a kendo instructor at the Yotsuya Police Station Dojo in Tokyo and a member of the ZNKR technical committee. At that time Mitsuzuka sensei had other Japanese students living here in the US, notably Kanai sensei, Kensho Furuya sensei, and soon Chiba Kazuo sensei.

To Japan (and back)

Like many of the early iaidoka, Meik Skoss sensei began studying Japanese martial arts in Los Angeles in the 1960s and in 1973 moved to Japan to further his aikido study. Skoss sensei connected with Draeger sensei and became a conduit for numerous American budoka who also came to Japan to study. Skoss began study of Shinto Muso-ryu with Shimizu Takaji in 1974 at the Rembukan; Toda-ha Buko-ryu with Muto Mitsu, and Tendo-ryu with Sawada Hanae in 1976 at the Shinjuku Taiikukan; and Yagyu Shinkage-ryūu with Yagyu Nobuharu in 1979 at the Nakana Taiikukuan. Skoss sensei’s martial arts curriculum vitae is extensive, but he may be best known for sharing his extensive knowledge and insight into both gendai and koryu arts, and as a scholar through his collaboration with Diane Skoss (nee Nordgren), an accomplished martial artist, writer, and editor in her own right.

Also beginning in Los Angeles, Mark Uchida had first seen Hiroshi Inagaki’s Chushingura (Toho, 1962) when he was a child and was immediately hooked on Japanese swordsmanship. He started training in kendo in 1973 and began studying iaido a year later. In 1979 while visiting Japan, he met Rev. Kan Shunshin who in turn introduced him to Hiroshi Onuma, sensei of the rigorous Keishicho Dojo, whose iai is a direct line from Nakayama Hakudo. While in Japan Uchida sensei trained with a number of legendary MSR instructors including Oda Katsuo sensei. Uchida sensei later became the first head of the AUSKF’s Iaido Development Committee.

Beginning in 1977 and running until 1981 another student of both Ueshiba and Mitsuzuka senseis, Chiba Kazuo, ran a private aikido study group at the Aikikai Hombu dojo in Tokyo which included iaido study with Mitsuzuka sensei at his Tokyo dojo. Americans who went to Japan to study as part of this program and returned to become outstanding sensei included Malcolm Shewan, Paul Sylvain, Lorraine DeAnne, Mike Skoss, Glenn Yoshida, Sheila Walker and Jay Dunkelman and later Bruce Bookman, Marion M. Taylor, Kensho Furuya, Diane Nordgren, and Art McConnell.

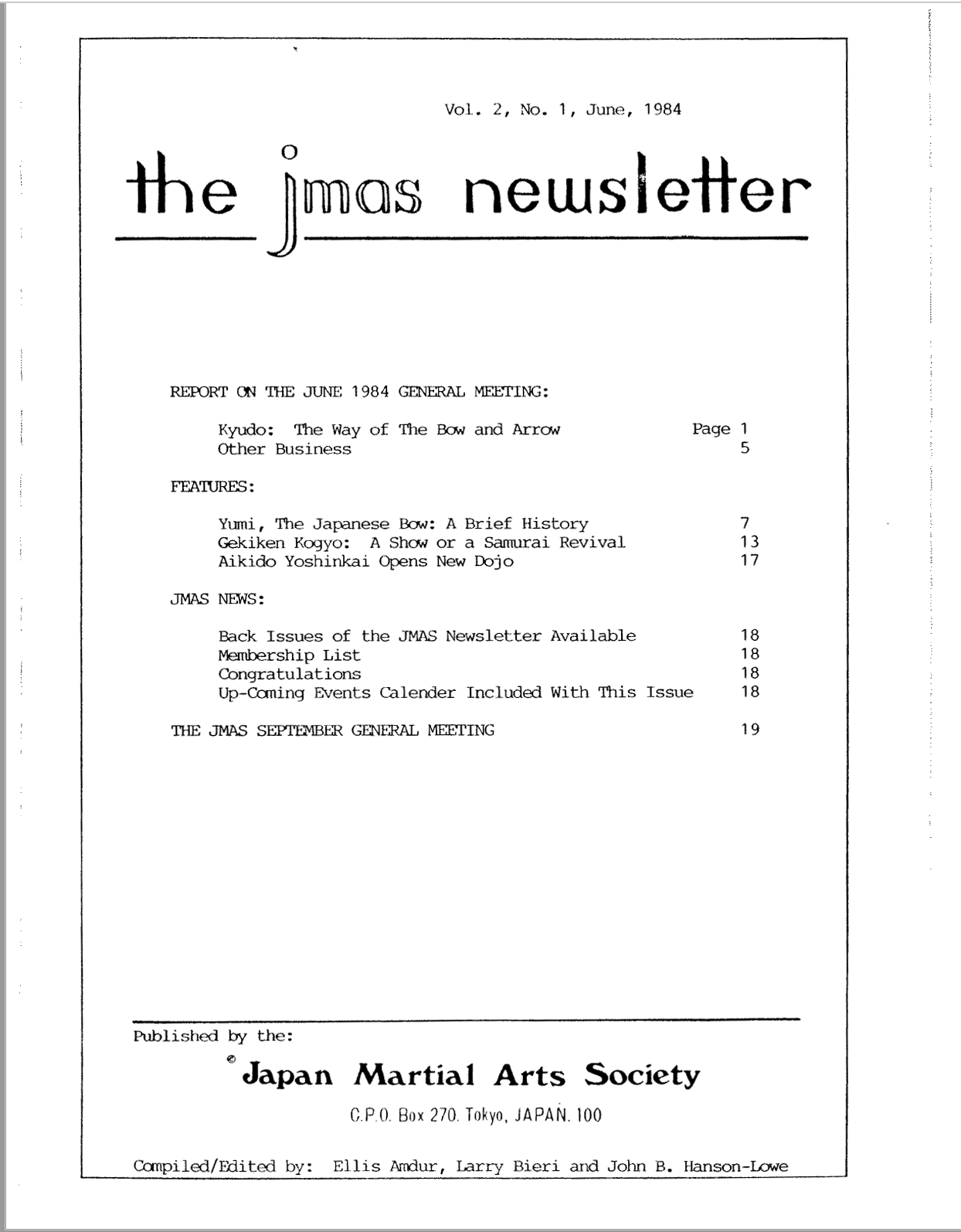

American and French students with Mitsuzuka sensei in 1978 (Didier Boyet)

Shortly after this in 1983 a second group of Americans studying in Japan, some formerly associated with Donn Draeger, that included Phil Relnick, Dr. Karl Friday, Brian Stokes, Don Trent, Dave Dimmick, David A. Hall, Ellis Amdur, Larry E. Bieri, Laszlo J. Abel, Ron Finne, Nyle Monday, John Ray, Chris Mulligan, Dale Schwerdtfeger, Rick Polland, David Hall, Darrell Bluhm, Nick Suino and Meik Skoss, formed the Japanese Martial Arts Society. While not exclusive to sword arts by any means, JMAS produced a quarterly English language newsletter on the arts these budoka were learning in Japan. This group studied a range of other budo including Mugai-ryu, Itto-ryu, Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu, Jikishinkage-ryu, Yagyu Shinkage-ryu, and Toda-ha Buko-ryu. And some students never returned.

Iaido study was in no way exclusive to NYC, Boston, SF and LA. Guy H. Power had begun studying the martial arts in 1968 in Bangkok, Thailand while his family lived there. “After we returned to the States in 1970, we were living in Charleston, South Carolina again where I finished my senior year of high school. My cousin introduced me to Mr. Albert C. Church who had just returned from Camp Zama, Japan. Incidentally, Church Sensei lived on the next street over and I often visited him. While transitioning from Tae Kwon Do to Mr. Church’s Shito-ryu, kenpo, and jujutsu, I found out he was a sandan in Mugai-ryu iaido, so asked him to teach me. I began my training in 1970 and continued for a year until my family moved to Illinois, where I continued to practice iai. I continued to practice by myself when I joined the United States Air Force from 1973 through 1978.” (Power / Aloia, 2022)

The Rocky Mountain Budokan was founded in 1965 by Iwakabe Hideki in Denver, CO as a karate dojo. In 1975 Iwakabe sensei returned to Japan to train in Muso Shinden-ryu and came back to the US in 1977 to teach and founded the Rocky Mountain Kendo / Iaido Federation.

JMAS Newsletter 1984

In the early 1980s Nakamura-ha Toyama-ryu was introduced to the US at the Jisso Center in Kaneohe, Hawaii by Rev. Kurosawa Kyugo of the Seicho-no-Ie church. Early students included Joe Cieslek, Loren Pelky, and Patrick Lineberger. They also studied the Yamaguchi-ha of Toyama-ryu and both Lineberger and Pelky had earned ranking by 1986. Dr. Stephen Fabian studied Yamaguchi-ha in Japan with Inoue Munetoshi sensei, a direct student of Yamaguchi sensei. In turn Nyle Monday, a student of the Donn Draeger, studied Yamaguchi-ha from Lineberger sensei. Dr. Karl Friday also studied Toyama-ryu while earning a Menkyo Kaiden in Kashima Shin-ryu.

In Canada, the Shidokan Kendo Club was founded by Douglas Tamaichi Funamoto in 1974. Iaido wasn’t officially offered by Fred Y. Okimura until 1987 but his students followed an expanded curriculum including iaijutsu, kenjutsu, and suemonogiri, and produced instructors Santoso Hantijo, Robert Miller, Dean Jolly, Lawrence Tsuji sensei, and Gilles Valiquette sensei, Funamoto Sensei's first student.

Also in Canada, Kim Taylor sensei who had started martial arts training in aikido in 1980 fell hard for iaido after studying with Mitsuzuka sensei during a 1983 aikido/ MSR iaido seminar at Paul Sylvain’s dojo in Amherst, MA. Taylor sensei continued to study with Mitsuzuka and Kanai senseis whenever possible and also with Toronto’s Stephen Cruise sensei, a senior student of Oda “Ken” Katsuo.

“I spent the next couple of years devouring everything I could in the form of books (there were no videos) on the subject and practicing what I knew (5 Shinden kata) with Bruce Morito, a fellow student. In 1987 that student found Ohmi sensei in Toronto and we actually did the “waiting at the gate” thing before he’d let us practice in the same room. He had stopped teaching because nobody hung around long enough to make the distraction from his own practice worth his while. When the two of us started showing up regularly Cruise sensei joined us from Etobicoke and we had the nucleus of a group..”

In May 1984 Dr. Nabeshima Kenshi sensei, Ishi sensei and Yamaguchi sensei, with ranking members of the Kendo Iaido Kyokai, gave what was perhaps the first enbu performed outside of a martial arts venue in America at the Dallas Museum of Art in Texas. That same year Otani sensei’s students began performing what became for many years an annual enbukai at the Brooklyn Botanical Garden’s Sakura Matsuri.

Brooklyn Botanical Garden’s 1984 Sakura Matsuri with Phil Ortiz and Deborah Klens-Bigman sensei on the right (Ortiz)

Around this time, Otani sensei and Mutsuzuka sensei had a falling out, leading Mitsuzuka sensei to create his own organization, the North American San Shin Kai, which was initially led by Paul Sylvain sensei and later between Sylvain on the East Coast and Chiba Kazuo on the West. This split between Otani and Mitsuzuka also led John Prough sensei to form the NY Japanese Swordsmanship Society. Over the next few years some of Otani sensei’s students left to start their own schools or to study other budo. Harvey Koenigsberg left to become a senior instructor at the New York Aikikai and founded the Woodstock Aikido Dojo. While earning her PhD, Deborah Klens-Bigman moved to Japan, studied Tenshinsho Jigen-ryu and became a Jun-Shihan in Shinto Hatakage-ryu Iai Heiho.

Before Chiba Kazuo sensei moved to southern California, another West Coast-based sensei who made an outsized impact on the community was Shimabukuro Masayuki who moved from Japan to Escondido, CA in 1976. Initially a karateka, in 1974 Shimabukuro sensei had begun sword study with Miura Hidefusa, the third So Shihan of the Masaoka-den of MJER and head of testing for the iaido and kobudo divisions of the DNBK. Shimabukuro sensei made semi-annual trips back to Japan to study with Miura sensei and brought him to the US to teach as well. In 1988 Shimabukuro sensei began teaching iaijutsu at the Pacific Martial Arts Foundation in El Cajon, California and soon helped establish the UC San Diego Iaido Club which is still going strong today.

Shimabukuro Masayuki sensei and Carl Long sensei (uncredited)

Reviewing Shimabukuro sensei’s arrival in the US offers an opportunity to discuss a previously noted issue that is still debated in the iaido community. Shimabukuro sensei came from a line that taught Muso Jikiden Eishen-ryu not as moving Zen or as a meditative practice but as a heiho. The foundation of this dichotomy of practice lies in the roots of iai, but its more recent expression began at the end of the war. Esaka Seigen sensei, a student of Kono sensei, taught MJER as a meditative practice, whereas Miura sensei, a student of Masaoka sensei, taught MJER as a heiho.

“Masaoka Sensei emphasized the point that solo iai practice was not enough to maintain any real martial efficacy and that the paired kata, as opposed to being ‘tacked on’, were an integral part of the curriculum and were essential to prevent iai from becoming ‘just a show for self-satisfaction where the enemy is forgotten’ (his words). ... This is why he referred to his art as ‘iai heiho’ as opposed to ‘iaido’, emphasizing its nature as a comprehensive martial discipline (sogo bujutsu).”

The dichotomy of practice is perhaps more profoundly understood comparing ZNKR Ken Zen iai with ZNTIR Toyama-ryu or other arts in which the combat aspect of sword practice are emphasized. Shimabukuro sensei was comfortable emphasizing jissen budo or combat effectiveness in his iaijutsu. Why? Carl Long sensei has noted that Shimabukuro sensei was of the postwar generation of Japanese budoka and didn’t carry the same stigmas about sword arts that many of his pre-war contemporaries did. There was also a connection that goes further back between Miura sensei and Nakamura sensei. Like Nakamura, Miura sensei was a budoka. In addition to iai Miura sensei was also adept at kendo, jujutsu, Okinawan kobudo, karate-do, jodo and suemonogiri. He was so proficient at cutting that upon seeing him perform suemonogiri in 1977 Nakamura sensei awarded him a hanshi and 8th dan in Toyama-ryu. Shimabukuro sensei was also a budoka and studied and taught all of Miura sensei’s arts.

“In short, the Japanese sword exists to perfect the heart and mind of its wielder through spiritual training ... ”

These topics are still issues for discussion, but the net result was that interest in more combative styles of iai such as the Masaoka den of MJER, Toyama-ryu, Nakamura-ryu and koryu sword arts grew. This appreciation of different kinds of iaido practice opened the doors for new teachers and new ryuha to thrive in the US. While this is in no way meant to be an exhaustive discussion of this dichotomy, I’ll leave the subject on the note that there are many points of common ground between these two approaches to iai training.

Similar to Shimabukuro sensei in moving from Japan to America and continuing the theme of sensei who emphasized jissen budo, in 1980, at the recommendation of Hayashi Kunishiro, a movie fight choreographer and head of the Wakakoma Action Club, Obata Toshishiro sensei moved to Los Angeles to pursue film acting opportunities. Obata sensei had studied Yoshinkan Aikido as a deshi of Shioda Gozo, but after seeing Nakamura sensei at a demonstration of several iaido ryuha, Obata became his student in Toyama-ryu and Nakamura-ryu. When he came to LA, Obata initially taught aikido at the Downtown LA YMCA but had been granted a Kanban by Nakamura sensei to teach Toyama-ryu in the US. Obata’s students were primarily Japanese businessmen living in southern California.

“The psychic dimension implicit in ritualized combat serves to sooth anxiety. The physical skills acquired lend at least an illusion of control over events in a hostile universe.”

In 1983 Obata sensei accepted his first dedicated iai student — an American — Guy H. Power. At this time, Obata sensei wanted to write a book on Toyama-ryu for American audiences. Power sensei, who was then stationed in Fort Irwin, CA drove up to LA every weekend to study with Obata and help research and translate the book. Completed in 1985 and published in March 1986, Naked Blade, a Manual of Samurai Swordsmanship (Dragon Books) was the first English language manual on Toyama-ryu Batto-jutsu. Hyperbole aside (Samurai?), the book followed the format of Nakamura sensei’s books by implicitly challenging the prevailing view of iaido as only solo practice, or that iaido doesn’t train in use of the sword as an actual weapon. In the book Obata also promoted tameshigiri using tatami, perhaps the first time that this was seen in an American publication. In the book, as a throwback to early Nakamura-ryu students, Obata sensei wore a Japanese Self Defense Force training uniform and a sword belt rather than an obi while demonstrating Toyama-ryu.

Within a year of the publication of Naked Blade, Obata released a second book, Crimson Steel, featuring a variety of previously unseen batto waza. Perhaps echoing Nakamura sensei’s move away from Toyama-ryu, Obata sensei moved away from Nakamura-ryu while creating his Shinkendo which incorporated batto waza from Hayashi sensei’s Wakakoma Club house style. Obata soon developed an American student base that included Nathan Scott, who would go on to become Shibucho in America for Ono Ha Itto-ryu. Power sensei earned his first and second dan with Obata sensei but was soon assigned to Camp Zama in Japan.

Reverend Furuya Kensho

Also based in Los Angeles, Daniel Masami Furuya, also known as Reverend Furuya Kensho, was a third-generation Japanese American who began training in the martial arts at age eight. Furuya sensei studied kendo, Itto-ryu, MSR and MJER with Takiguchi Yoshinobu, Ebihara Tadao and “Tiger” Mori sensei. While earning his undergraduate degree at Harvard, Furuya had studied aikido and MSR with Kanai sensei in Boston, and after graduating college in 1969, he moved to Japan to study at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo and studied MSR with Mitsuzuka sensei. While in Japan, Furuya studied Zen with Kenko Yamashita, a classmate of Nakayama sensei and an iaido adept. In aikido Furuya sensei also gravitated to Mitzuo Saotome sensei, who was also adept at Ono Ha Itto-ryu iaijutsu (in 1975 Saotome sensei and his senior student, Ikeda Hiroshi, left Japan to settle in Florida, where they created their own aikido organization which emphasized weapons use — aiki-jo, aiki-ken and iaido). Furuya sensei returned home to Los Angeles in 1974 to teach aikido, but it was not until 1984 that he opened his Aikido Center of Los Angeles offering instruction in aikido and Muso Shinden-ryu. The design of the dojo was so classic that it was “stolen” for movies such as The Matrix and Rush Hour 2.

Furuya sensei was a voracious reader and became an expert on the typology and chronology of nihonto. In the ensuing years since founding his dojo he authored Kodo: Ancient Ways; created a video series The Art of Aikido and founded the Kenshinkai or Los Angeles Sword and Swordsmanship Society. In 1986, Furuya sensei came across a classified advertisement in a local newspaper that read “Japanese Swords wanted, cash paid.” A few days later he would make the acquaintance of Hataya Yoshitoki. Hataya sensei had come to America to buy nihonto that had been brought to the US without authority. Speaking little English, Hataya sensei traveled across the country placing the same advertisement in local newspapers as well as attending local gun and knife shows. Hataya made a business of refurbishing these nihonto, having them officially appraised and licensed, and selling them to new owners back in Japan.

When Furuya sensei learned that Hataya was highly ranked in Toyama-ryu, he asked Hataya to teach the art to his students. From 1986 to 1990, a senior student of Furuya sensei’s, Douglas Firestone, was tasked with learning the new art and teaching it in between Hataya sensei’s visits. Already ranked in MSR, Firestone sensei along with Power sensei, joined the first Americans to earn rank in Toyama-ryu Batto jutsu here in the US.

In 1985 Nakamura made a video for the home video market in Japan, but it wouldn’t arrive in the US market for another 15 years! In 1986 Nakamura wrote his fourth book, Battodo (Japan). That same year Nakamura sensei also traveled to the US and gave an embu at the Sakura Matsuri in Seattle, Washington. This was the first of several visits by Nakamura sensei to the US including a 1988 television demonstration, but unfortunately there’s no record of any of these events.

Also in 1986, Hataya sensei, while conducting his annual nihonto procurement expeditions met Bob Elder, owner of East Coast Martial Arts Supply (back when buying gear required going to a physical store or using a mail order catalog). Elder sensei was a karateka, a lifelong Japanese weapons enthusiast and also had an interest in nihonto. Elder sensei found a kindred spirit in Hataya sensei, and under Hataya sensei’s tutelage over the next years Elder studied nihonto appraisal and grading and built a lifelong friendship.

In 1987 in Canada Kim Taylor sensei opened the Sei Do Kai Dojo at the University of Guelph offering instruction in MJER and began what became a series of annual iai seminars starting with Haruna Matsuo sensei featuring sensei from around North America and Japan.

In April of 1987 the organizers of the Seattle Cherry Blossom and Japanese Culture Festival invited Nakamura sensei and several other Japanese iaidoka to come to Seattle to perform embu at the festival. Tom Bolling sensei, a deshi of Pat Yoshitsugu Murosaka sensei, was charged with showing Nakamura sensei around Seattle while he visited every kendo dojo he could to meet their sensei and give lessons. This was the first of two or three visits to America that Nakamura sensei did on his own (and are hence, not well documented).

“Nakamura Sensei made no bones about having been an officer in the Japanese Army’s Kirikomeitai (Kempeitai?) in Manchuria. This special “psywar” unit simply attacked the Chinese with drawn swords and terrorized them utterly.

Well, Nakamura Sensei’s direct words to us were that he had had an enlightenment experience and renounced the use of swords to hurt others. He said that’s why he had named his system “Happogiri Batto-Do” and not “Batto-Jutsu”.... because he intended that it should only be used to cultivate the “Katsujin-Ken” and never again the “Satsujin-Ken” as in his previous, deeply mistaken, period.”

The Heisei emperor and empress, January, 1989

1989 began with the death of wartime Showa emperor Hirohito, and his son Akhito becoming emperor and initiating the Heisei era.

As the year progressed there were a number of quiet events that would soon come to have positive impact on the growth of iaido in the North America. Kim Taylor sensei founded The Iaido Journal with a distribution list of 16 dojos across the United States and Canada. The dojo were organized for potential visitors according to style — Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu or Muso Shinden-ryu although at the time between Taylor’s Sei Do Kai dojo and the University of Guelph Iaido Club both ryuha were offered as well as Japan Kendo Federation’s Sei Tei Gata Iai.

1989 was also the year that Panther Productions released their first home video market iaido VHS videotape featuring Yamaguchi Katsuo sensei performing Muso Jikiden Eishin-ryu; in Hawaii the Daihonzan Chozen-Ji published an English translation of Takuan Soho’s Fudochi Shinmyoroku. a collection of letters between Zen Master Takuan Soho (Tenji) and the master swordsman Yagyu Munenori, who lived during the 1600s; in Pennsylvania, karateka Carl E. Long sensei opened his own dojo, the Sakura Budokan and in the Toyama-ryu Batto realm, Furuya sensei began planning the very first Toyama-ryu Batto-jutsu enbukai to be performed in the United States.

Also in the Toyama Ryu realm, in Japan in November 1989, Stephen Fabian sensei achieved a first for an American when he became the Toyama Ryu Iaido All-Japan Champion in the Men's Shodan/Nidan Division,

If it isn’t too hyperbolic to say, interest in iaido in the US was about to explode.